Travel across Texas and you’ll find resilient communities with stories of overcoming hurricanes, flooding, tornados, droughts, wildfires, and extreme cold waves and heatwaves. Each year, Texas leads the US with more disasters than any other state.

Travel across Texas and you’ll find resilient communities with stories of overcoming hurricanes, flooding, tornados, droughts, wildfires, and extreme cold waves and heatwaves. Each year, Texas leads the US with more disasters than any other state.

In many ways, Texas offers a wealth of knowledge when it comes to disaster response. Resilient communities and local leaders can point to a particularly bad year and say, we got through it together. But the rising number of costly disasters, exacerbated by climate change, demands stronger preventive measures.

Dr. Michelle Annette Meyer, Director of the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center and an Associate Professor in the Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning Department at Texas A&M University, works with communities and non-profits to approach disasters differently. As a social scientist, she understands disasters not as surprise emergencies, but as planned events that we can prepare for well in advance. Through preparation, we can build more resilient communities.

“Since Texas has the most disasters of every state, we are the most knowledgeable about how to respond to them,” says Dr. Meyer. “We have to do better to mitigate and prepare for them because Texas will see every type of hazard that climate change brings.”

She stresses that each year, more communities experience back-to-back disasters. Hood County, for instance, experienced a tornado in 2013 and a flood in 2014. These are no longer freak events, but rather, regular occurrences. Dr. Meyer predicts costs to climb. “I think we’ll start seeing trillion-dollar disaster years instead of billion-dollar disaster years,” she warns.

In 2021, the US experienced 20 disasters that each cost more than 1 billion dollars in damages. In the last five years, the US has logged 56 different billion-dollar disasters. And the losses aren’t exclusively material. More than 600 people died in these billion-dollar disasters in 2021 alone. Disaster mitigation will not only save property but also save lives. Fortunately, there are steps we can take today to prepare.

How can you prepare for a disaster?

Dr. Meyer offers tips for how Texas households can plan for disasters:

- Make a social plan: If you have to evacuate, who will you stay with? If you have to relocate, who can you live with? How will you travel? Discuss plans with your extended family and friends to make sure everyone has a place to go and a way to get there.

- Save and insure: Due to inflation and high housing prices, many Americans are now underinsured and would not be able to rebuild the same house if it were destroyed today. Check your insurance annually and learn what your mortgage company offers in the case of a disaster. If possible, set aside some savings to cover potential losses.

- Set aside essentials: Save insurance cards, emergency contact information, medications, children’s medical information (including vaccine documentation) and pet records (like rabies tags) in one container. You’ll be glad to find all information in one place should you need to evacuate.

- Document your belongings: For insurance purposes, take photos of every room in your house, and back up the photos to the cloud. It’s much easier to file insurance claims if you have photos of your home and everything in it.

- Download the weather app: Make sure you can receive information from your local weather station in real-time. Set up notifications for extreme weather alerts.

- Connect with your community: Volunteer with disaster-related organizations, and discuss disaster plans with your employer, schools, religious organizations, and other membership groups. Each of these entities has a role in supporting the broader community to recovery.

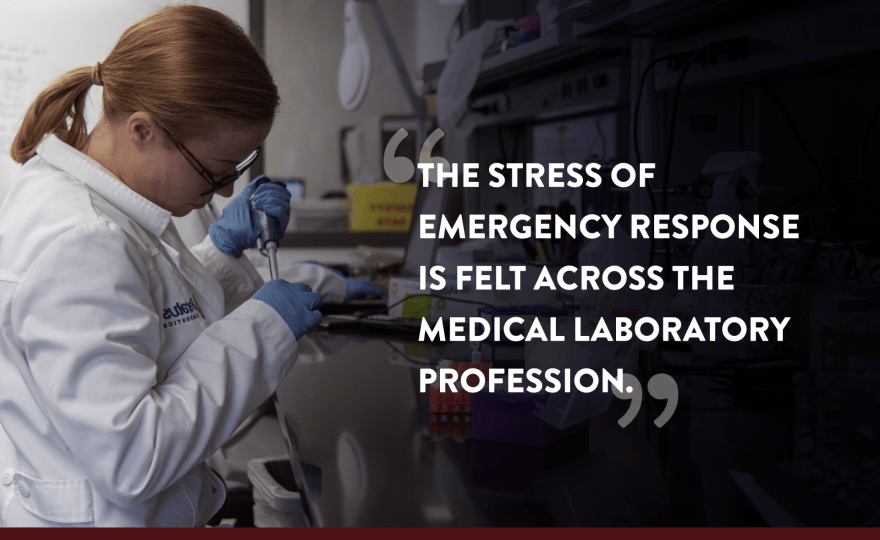

Disasters worsen existing inequality

Of course, disaster mitigation looks differently for households of varying incomes. “Any inequalities we see in society will show up in disasters and potentially get worse,” explains Dr. Meyer. Biased policies make it easier for homeowners to claim money post-disaster than it is for renters, who are more often from racial minority groups. Landlords receive less funding than homeowners to rebuild, so disasters further limit affordable housing options. On top of this, undocumented immigrants do not qualify for FEMA or other federal aid programs. Instead, many look to the nonprofit sector for support. At the end of the day, minority groups are more severely affected. It will take all of us to plan for disasters and build more resilient communities.

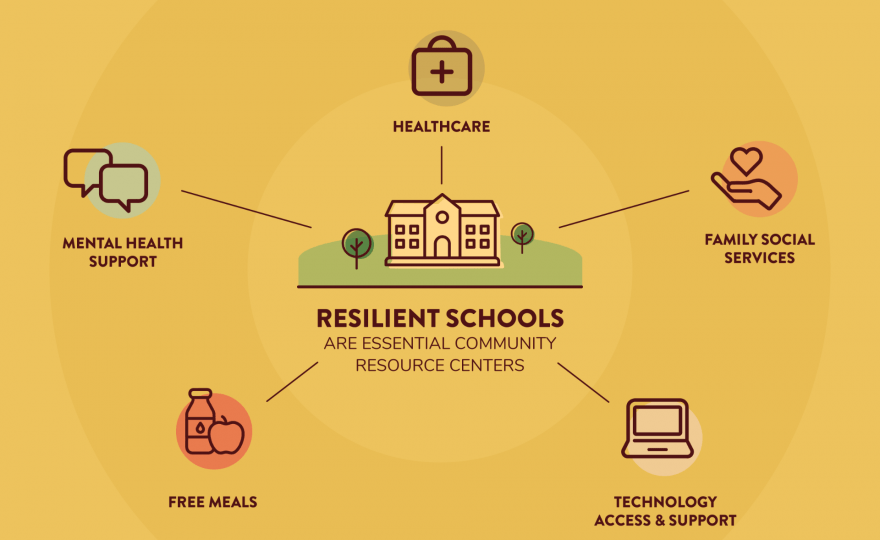

Community networks for disaster mitigation

Dr. Meyer has seen the strength of local nonprofits in filling equity gaps in disaster response. Habitat for Humanity, an international organization with 68 local affiliates in Texas, expands its programs following a disaster. Local NGOs also support renters in the process of becoming homeowners. The nonprofit sector often facilitates the social network building that strengthens a community’s disaster preparedness.

“Before a disaster, you need everyone focused,” says Dr. Meyer. “Communities that keep those networks going after the disaster are better prepared to mitigate the next one.”

Learn more about disaster mitigation

- The NAACP’s Action Toolkit, In the Eye of the Storm, builds equity into the four phases of emergency management: prevention and mitigation, preparedness and resilience building, disaster response and relief, and recovery and redevelopment.

- The Center for Disaster Philanthropy provides expert resources, blogs, and webinars on strengthening local humanitarian response, how to support long-term recovery, approaches to recovery in rural communities, and more.

- The American Planning Association’s Hazard Mitigation Group publishes reports that can be applied to disaster preparedness and disaster response at the community level.